Whenever I meet new physical therapists, I am always blown away by their compassion for their patients and their deep-seated drive to help those patients heal. PTs—like many other healthcare providers—naturally operate from a state of altruism. We genuinely care for our patients and want to help them achieve their health goals, so we work 12-hour days, bring our documentation home, and still make time for patient phone calls and emails.

But, as they say, the road to hell is paved with good intentions, and even though we care about our patients—even though we’re invested in their healthcare journey—we cannot (and do not) serve our patients equally. The reason? Our country’s institutions, including the massive institution of healthcare, are plagued by systemic racism and systematic prejudice. This isn’t a new concept, but recent events have brought it back into the limelight.

Some of you may have had a knee-jerk reaction to the end of that last paragraph. “I’m not racist. I treat all my patients equally—and I’m a good person!” But, the reality is that racism doesn’t follow a strict “good versus bad” dichotomy. Good people can (and do) participate in racism every day. It may not be on purpose, and you may not realize that it’s happening, but the foundations of our society are cemented with inequity. Black patients and other patients of color, in many different ways and for many different reasons, do not receive the same quality of care as white patients. And that is why we must talk about racism—it is a public health crisis that stands to affect the future of the PT industry, and we have a moral obligation to fight it.

I recognize that this can be an uncomfortable topic and that the PT industry is busy trying to rebuild in the financial aftermath of COVID-19, but I invite you (maybe even implore you) to sit in that discomfort. We have an opportunity to learn, grow, and improve ourselves and the world. But we must be willing to look at the hard facts, accept uncomfortable truths, and put in the work to fix what’s broken.

Let’s start with those hard facts and truths. I’m going to raise a lot of provocative questions, make the case that we are not doing right by our patients, and highlight the countless opportunities we have to do better.

The PT profession is not diverse.

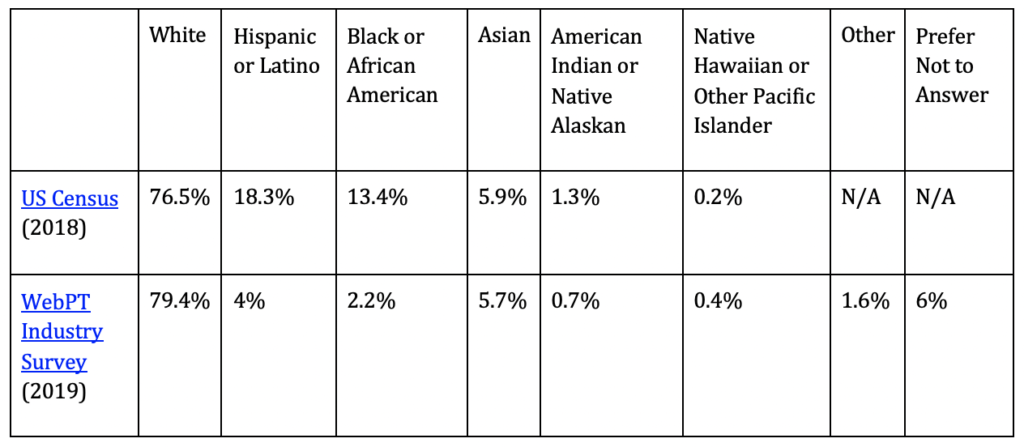

No matter which way you slice it, the racial and ethnic makeup of the PT profession does not match the racial and ethnic makeup of the United States. I’ve shared these statistics before, but I believe they bear repeating.

As you can see, there are enormous disparities between the makeup of our country and the makeup of our professional workforce—specifically when you’re looking at the number of Hispanic or Latino and Black or African American therapists. According to WebPT’s annual industry survey, only 6.2% of our workforce identifies with one of these groups, when together they total more than 25% of our country’s overall population.

APTA’s Racial Diversity

The APTA has previously said that 88% of its member base is white. To its credit, the APTA has sought to improve racial and ethnic disparities in the PT profession, but the racial disparity inside of the organization itself remains. How is our professional association supposed to protect and advocate for all therapists when entire groups of people are missing from, or underrepresented within, its ranks?

Education Programs That Promote Diversity

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t want to specifically pin the blame for the lack of diversity on clinic owners and APTA leaders, because frankly, even the best-intentioned leaders will have difficulty hiring diverse staff. This problem stems from the PT hiring pool, which is mostly homogenous; only a small number of minority students ever choose the PT career path. I think it’s worth asking ourselves why that’s the case.

Are our entry standards for graduate school too high? Does the degree cost too much? Are our recruiting efforts targeting diverse student populations? Is this a vicious cycle in which the overall physical therapy “brand” does not appeal to people of color due to the lack of diversity in the industry?

We must look critically at our profession from all angles if we want to fix this issue.

A lack of diversity makes it difficult to connect with patients.

We’ve established that the PT profession is not diverse—but does that really affect our ability to treat patients? The short answer is yes. The US patient population is growing more diverse by the day, and a more diverse staff will be better equipped to handle their unique needs. After all, according to this article from St. George’s University, “when a patient cannot find providers that resemble them, their beliefs, their culture, or other facets of their life, it may delay or prevent them from seeking care.”

To be clear, I don’t believe that providers should only treat patients who look like them (that would be a whole different problem), but our cultural homogeneity does affect patients’ access to care. Earning trust and forming strong, collaborative relationships with our patients is integral to their success, and while we can certainly improve our own ability to do that by recognizing and taking ownership of our implicit biases, we must also remember that our patients are human, too—and, as such, have their own implicit biases that influence their healthcare choices. So, we must ask ourselves, are patients comfortable seeking care from a provider who doesn’t look like they do or who is not a part of their community? I’m willing to bet that, for many patients, the answer is “no.” That’s why I believe it’s so important for patients to have access to providers who are familiar with their community, culture, and even language.

Access to Care

Additionally, a lack of diversity could end up limiting patients’ access to healthcare services. I mentioned this in the previous article I wrote, and I think it’s worth mentioning again. Minority providers choose to work in Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) “to a disproportionate extent” according to this Health Affairs research article. If encouraging diversity helps us reach and serve the patients who need us most, then we must prioritize diversity initiatives.

Cognitive Diversity

It’s also worth noting that provider diversity does more than make patients feel more comfortable in the clinic. When you hire people from a multitude of different backgrounds and cultures, you also support cognitive diversity or—as a Forbes Councils Member put it—“the inclusion of people who have different ways of thinking, different viewpoints and different skill sets in a team.” The best solutions and strategies typically come to light when you have a think-tank of experts who each approach a problem in a slightly different way—and that applies double on the clinic floor. When a clinic or local association has a wealth of cognitive diversity, PTs will naturally collaborate and learn from each other, and as PTs grow and improve their skill set, patients will reap the rewards.

A variety of socioeconomic barriers limit care access for black patients—and this affects their health outcomes.

Making an effort to improve the diversity in the PT industry is a great place to start—but it’s only one small piece of the inequity puzzle. Even if every clinic in the country were a paragon of excellence in diversity, black patients still would not receive the same quality of care as white patients.

Low-Quality Insurance Coverage

Black patients, on average, have consistently less (and worse) insurance coverage than white patients. And when patients have poor insurance coverage, their PT coverage is usually minimal—at best. Furthermore, without good coverage, patients are less likely to seek out PT as an avenue of care—and they’re certainly less likely to stick around until discharge. And actually, this problem extends beyond black patients: Hispanic patients, Native patients, and some patients from specific Asian populations all have less (and worse) insurance coverage than white patients.

Less Economic and Social Flexibility

Black patients also often have less economic and social flexibility. On average, white families have ten times the wealth of black families, and that wealth provides countless opportunities that directly (or sometimes indirectly) improve health. With more wealth, you might have better access to technology, which would help you attend telehealth appointments. You might have more reliable transportation, which would help you get to and from in-person appointments. More wealth could open the door to different exercise options: you could get a gym membership or invest in good running shoes that help prevent injuries. More wealth even helps you buy healthier food.

Black communities also often suffer from underinvestment, a holdover from the racially motivated redlining that occurred in the 1930s. This limits the resources (including the health resources) that residents have access to at any given time.

Higher Incidence of Comorbidities

We also cannot ignore that the black patient population has a significantly higher rate of comorbidities (e.g., asthma, diabetes, obesity, and hypertension) than the white population. Comorbidities often complicate illnesses and negatively impact health outcomes—something we’ve observed with COVID-19.

Impact of the Opioid Crisis

Even the opioid crisis is beginning to more heavily affect the black community. In the beginning, we often painted the opioid crisis as a white problem—likely because, as PBS reports, white Americans account for roughly 80% of opioid overdoses. However, our white community-centric anti-opioid advocacy has left black communities in the dust. Now, according to the CDC statistics, the mortality rate in black communities is beginning to rise faster than the mortality rate in white communities.

Black patients are subject to the effects of medical and unconscious bias.

Let’s imagine that, by some miracle, we’ve solved the diversity problem in the PT field, and we’ve successfully addressed the social determinants of health that create inequities among our patients. We would still have more work to do, because black patients are also often subject to medical and unconscious bias.

Medical Bias

Racially motivated medical bias has roots that stretch back hundreds of years. Medical professionals used to believe that there were physiological differences between white and black humans (something we now know is unequivocally false). Using that foundation, those professionals claimed horrifying things like:

- Black skin was thicker than white skin;

- Black people did not feel as much pain as white people; and

- Black people’s blood coagulated faster than white people’s blood.

Again, these are not based in real scientific evidence, yet some of those beliefs are held by medical professionals to this day. In this 2016 study of white medical students, researchers found that half of the students believed at least one racist medical myth about black patients.

And that has real consequences; it’s a well-documented fact that black patients are underprescribed pain medication. Think of that in terms of our job as PTs: it is our duty to help patients manage and reduce their pain. If these medical biases creep into our treatments, then we’re hurting the people who most need our help.

Unconscious Bias

Black patients (and other minority patients) are also subject to the nastier side of unconscious (or implicit) bias. Unconscious biases are the shortcuts that our individual brains use to filter, sort, and store the information that we collect every day. Unfortunately, these shortcuts use intuition and generalization instead of objectivity, which means our biases often point us in the wrong direction. Our biases can lead us to believe that women are less capable, or that black men are too angry—both of which are not only plain wrong, but also damaging to our patients: “Implicit bias was significantly related to patient–provider interactions, treatment decisions, treatment adherence, and patient health outcomes.”

We all have unconscious biases that affect everything we do. These biases impact our relationships, how we interact with the world, and even the way we treat our patients. We must do everything in our power to recognize these biases, because even if we can’t eliminate them, we can actively work to mitigate them.

Mitigating Bias

Start by teaching yourself, your coworkers, and your staff about implicit bias—what it is, why everyone is subject to it, and how it affects patients. Learn about different cultures; then, study the National Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) Standards and take them to heart. Finally, try to employ anti-bias exercises when treating patients. This source recommends a handful of such exercises, including stereotype replacement (consciously avoiding stereotypes and making an effort to individuate your patient) and partnership building (reframing interactions as collaboration instead of communication between a high- and low-status person).

We can’t advocate for universal PT brand awareness if we can’t speak to the whole population.

I am passionate about solving PT’s grand 90% problem (i.e., 90% of patients who could benefit from physical therapy never receive it). If we could get even 50% of those patients into our clinics, I genuinely believe we could change the healthcare system as we know it. But how are we supposed to transform society when we aren’t reaching a substantial portion of that society—and when we can’t even promise that all patients will receive the same level of care?

Think about it: if fewer black physical therapists open practices or are employed by clinics in their communities, how will the people in those communities get exposed to the benefits of PT? How will they learn about what PTs do and how physical therapy can help them? And how can we convince those communities to get PT services when there are so many barriers to overcome before they even walk through the door?

If we ever want to solve the 90% problem, then we must confront these realities—and take steps to change the status quo. There’s a lot to be done to solve this problem, but we can start by:

- reflecting on how we think about, and interact with, our patients,

- mitigating our biases (through some of the steps outlined above),

- advocating for more diversity in PT programs,

- advocating for better insurance coverage of PT,

- fighting for better social support for those who need it, and

- adjusting our strategy for fighting the opioid crisis.

Taking just one of these actions is a step in the right direction—toward meaningful change.

Accountability can be uncomfortable—but we will be better for it.

Accountability is uncomfortable. No one wants to look at themselves and acknowledge that their actions (or inactions, for that matter) may have harmed other people, but it’s something we must do for the sake of our communities. We can do better.

Hidden Hypocrisy

I am not exempt from that. I can do better—and so can WebPT. This latest push of the BLM movement has forced me to reconcile my beliefs about equality and fairness with my lack of action.

We at WebPT have always known that pushing for diversity is important, but we never placed it at the highest priority level of our agenda. In recent weeks, we’ve solicited and received some critical feedback—both internally and externally—that revealed numerous areas where we can improve. For example, we’ve celebrated Pride for years—but we’ve never celebrated Black History Month, Women’s History Month, National Native American Heritage Month—the list goes on. Why did we single out Pride as our badge of honor for celebrating diversity?

We have already changed our recruiting process to address some harms; we no longer ask candidates what they made at their previous job, as this continues the cycle of wage disparity among people of color and women. And we’re not stopping there—but we’re not taking a shotgun approach to changing our policies, either. Rather, we are being thoughtful, humble, and introspective—gathering feedback from our employees, vendors, and other stakeholders. We’re also seeking guidance from DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) experts who will help us create a comprehensive company plan that also adheres to our core values. This plan will also include important changes to the WebPT application so that our products represent our culture as well.

We’ve always been proud of ourselves for curating a warm environment that welcomes everyone with open arms—but that pride blinded us from our weak spots. Going forward, we’ll be more intentional about promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion instead of waiting for a crisis to put it front and center.

Compassionate Culture

No one wants to walk on eggshells day-in and day-out and constantly worry about saying or doing the wrong thing. That’s where a culture that values accountability comes in for the save. Everyone is going to misstep, and your clinic’s culture needs to encourage graciousness and open, safe communication. Everyone—especially organizational leaders—should feel comfortable pointing out mistakes when they see them. And everyone needs to know how to take criticism in stride, be vulnerable sharing feedback, and use this dialogue to improve future actions. We’re all learning, and we need to build each other up and have the humility to know when we’re wrong.

_____________

Systemic inequity is not a problem that we’re going to solve overnight. It’s complicated and messy, and it has seeped into nearly every facet of our everyday lives. But, I believe we have the tools and the agency to do better—to be better as individuals and as a profession. I believe we can create a better environment for our patients and our community. I believe that a better world is possible. Do you? Where are you going to start?

––– Comments

Paul Leverson

Commented • July 30, 2020

Heidi... Thank you for your thought provoking article. But I don't agree with many of your assumptions or suggestions and it is possible some of the things I write in my reply you may not agree with. About 74% of all physical therapists are female. About 50% of all people are female. I am a male and feel no specific animosity towards myself...despite working in a predominately female profession. It has never dawned on me that the PT profession should target more males to get into the profession. In fact, just the opposite. We should not be targeting anyone for the sake of being more or less diverse. It is ironic that, in seeking to become more diverse, our efforts and our emphasis begins to slant towards certain preferences that, in essence, make them racist. If WebPT is looking to become more diverse, and I, or my wife (both caucasian and Christian) apply for a job there, will you be looking at our qualifications...or our race...or our sex...or our religious belief...or what. Will we, in essence, be "less qualified" because we are not of the right diverse profile? It is incredibly insulting to even propose something like this. Instead, shouldn't "content of character" and skill set be the determining factors? It would never dawn on me that race, sex, ethnicity, religious preference, etc. should factor into any of my decisions on how I relate to someone...much less if I should hire them. Remember, racism is either the diminishing of one set group of people based on their race...or the elevation of that one set over another. In our pursuit to be better, let's not do the latter. With that said, we are all different...and should be treated individually. Racism is the ugliest of blemishes of the human heart which stems specifically and only from the heart of the individual who decides IN THEIR HEART that one person has more value over another. It is the worst affront to the One Who has created us. All life if precious. All people have value. Equal people are not free...and free people are not equal. We are all different...all imperfect...all fallen and flawed...all able to learn and benefit from others. And I have love for all of them...Because I have first been loved.

SHELLEY KOZEL

Commented • July 9, 2020

Very well said. I have seen implicit bias in action.