Whether we’re eight or eighty-five, most of us have heard the same advice: “Lift with your legs!” The warning comes from a long standing belief that bending at the waist, especially with some degree of rotation, puts your back at risk. There’s some truth in that. But does that mean keeping your back straight and knees bent is always the safest or most efficient way to lift? For everyone? Every time?

As we know, there are no “one-size-fits-all” human bodies. So maybe it’s time to rethink the idea that there’s one “right” way to lift.

Rethinking the “Right Way” to Lift

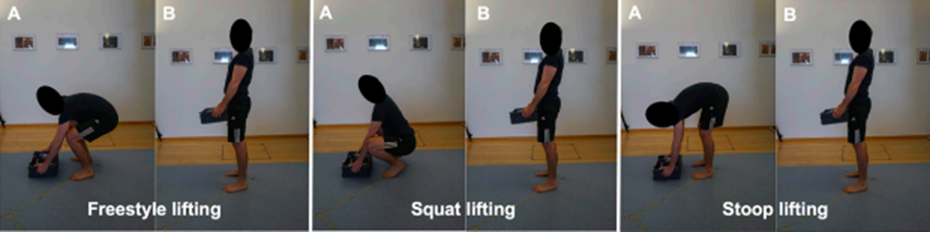

A fascinating study by von Arx and colleagues (2021) looked at three common lifting styles: (von Arx et al., 2021)

- Stoop lift: bending over at the waist with a flexed spine.

- Squat lift: knees bent, back “straight,” using the legs.

- Freestyle lift: a natural mix of both.

Image from von Arx, L., Liechti, M., Meier, M. L., & Schmid, S. (2021) (von Arx et al., 2021)

Using advanced motion capture, the researchers measured how much compression and shear force each style placed on the lumbar spine. But before diving into their results, it helps to revisit why backs hurt in the first place. (Bae et al., 2024; Lam et al., 2023)

Why Low Back Pain Happens

Back pain is incredibly common, almost inevitable at some point in life for most adults, and can stem from many sources (Hartvigsen et al., 2018). For this reason, as clinicians, it’s useful to evaluate both diagnostic data and subjective patient reports through a biopsychosocial lens (Schreiber, K. L., et al. 2025). Recognizing that multimodal receptor inputs are continuously shaped by conscious and unconscious psychological states, and by the environmental context in which these processes intersect, we can fathom how pain generation is something far more nuanced than an indicator of simply issue breakdown.

Applying this thought process to the spine, we see it more than just a stack of bones; it’s both a load-bearing column and a neural communication hub. When the brain perceives a threat-physical or emotional, it can trigger a protective response. That’s when pain emerges.

A Mechanical Perspective

Mechanically, back pain often involves repetitive compression and shear forces that exceed tissue tolerance. Over time, the discs lose hydration and flexibility, the facet joints become irritated, and bone structures remodel to handle stress. This “degenerative cascade” can create pain, but interestingly, similar changes often appear on MRI scans of people with nosymptoms. That tells us tissue damage alone doesn’t explain pain. (Adams & Dolan, 1996; Gallagher & Marras, 2012; Noailly et al., 2023; Park et al., 2024) (Brinjikji et al., 2015; van der Graaf et al., 2023; Fujii et al., 2022)

The Nervous System’s Role

Pain is ultimately a neurally constructed experience, shaped by how the brain interprets incoming sensory signals (Armstrong & Herr, 2023). Nerve endings (nociceptors) in discs, joints, and ligaments send danger signals to the brain when tissues are stressed (Kuner & Flor, 2021). Because different nociceptors transmit information at different speeds—fast A-delta fibers producing sharp, localized warnings and slower C-fibers creating dull, lingering aches—pain can feel very different depending on which pathways are active, much like the difference between stepping on a tack versus realizing you’re sunburned hours later (Armstrong & Herr, 2023).

When those slower nociceptive fibers are repeatedly activated, they can make the nervous system hypersensitive, a process known as sensitization (Kuner & Flor, 2021). In this state, even normal movement can start to feel threatening because the threshold for signaling danger has dropped (Yuan et al., 2024). In long-standing pain, immune cells can also continue releasing inflammatory chemicals that maintain this heightened sensitivity, allowing pain to persist even after tissues have healed (Kuner & Flor, 2021).

How Pain Changes Movement

When nerves become sensitized, they alter how muscles fire. As a means of increasing protection while trying to maintain movement efficiency, the nervous system can inhibit some muscles while making others hypertonic. The result? Stiffness, imbalance, and more mechanical stress. But these changes vary widely, and can be unpredictable population wise. As researchers Paul Hodges and Shaun Tucker described, people “move differently in pain”, creating sub-conscious, self-organizing strategies designed to protect a sensitive area in the short term; to maximize immediate survival, even if it comes at the cost of long-term tissue health. (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2022) (Hodges & Tucker, 2011)

The Layers of Low Back Pain

Put simply, back pain reflects an interaction between tissue stress and neural modulation. Mechanical breakdown initiates local irritation (Adams & Dolan, 1996; Gallagher & Marras, 2012; Noailly et al., 2023; Park et al., 2024). Peripheral sensitization lowers the threshold for pain signals (Kuner & Flor, 2021). Motor adaptation changes muscle coordination (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2022). Central sensitization maintains pain even after tissues heal (Yuan et al., 2024).

Understanding these layers helps clinicians move away from thinking of pain as “discogenic” or “arthritic.” Pain is not a direct readout of damage—it’s the brain’s protective response, influenced by biology, psychology, and context (Hartvigsen et al., 2018; Schreiber et al., 2025). A person can have intense pain with no visible injury, or little pain despite significant imaging findings (Brinjikji et al., 2015; van der Graaf et al., 2023; Fujii et al., 2022). This is why education, reassurance, and graded exposure to movement are just as vital as traditional “hands-on” treatments (Hartvigsen et al., 2018).

What the von Arx Study Found

So, back to lifting. The von Arx team studied how 30 healthy adults lifted a 15-kilogram (33-pound) box in each of the three postures, measuring compressive and shear loads at different spinal levels (von Arx et al., 2021). Here’s what they discovered: stoop lifting created lower compressive loads but higher shear forces, especially in the upper lumbar spine (von Arx et al., 2021). Squat lifting reduced shear forces but increased compressive load—particularly at L5/S1, the area most prone to disc and spondylolisthesis injuries (von Arx et al., 2021). Freestyle lifting—the most natural and fastest technique—produced the highest total loads overall, especially at L5/S1, though with lots of individual variation (von Arx et al., 2021).

To summarize:

Stoop = less compression, more shear

Squat = less shear, more compression

Freestyle = overall highest load but most adaptable

Matching Lift Style to the Person

Does that mean one style is “best”? Not really—it depends on the person and their underlying condition. Disc herniation: since herniations are aggravated by shear forces, a squat lift (which minimizes shear) might be safer (Gallagher & Marras, 2012). Osteoporosis: because fragile bones can’t handle high compression, a stoop lift (less compressive) could be better (Kirkaldy-Willis & Farfan, 1982). Spinal stenosis: extension tends to worsen symptoms, so stoop or freestyle lifting may feel more comfortable (Fujii et al., 2022).

The key point: posture should match the individual’s needs and tolerance, not a generic rule (Hartvigsen et al., 2018).

Spines are often Stronger Than We Think

It’s easy to treat the spine like fragile porcelain, particularly in seniors, but research shows it’s built to handle enormous loads (Gallagher & Marras, 2012). On average, the lumbar spine can withstand stresses of over 400 pounds of shear force before failure, and many everyday movements stay well below those limits (Adams & Dolan, 1996). Even repetitive loading, when under moderate force, is tolerated thousands of times without damage (Adams & Dolan, 1996).

Of course, when pain is present or tissues are healing, capacity may drop, but the overall message is clear: spines are resilient. They’re not waiting to break every time someone bends forward (Hartvigsen et al., 2018).

Movement as a Self-Organizing System

When someone picks up a box or a grandchild, they immediately integrate sensory feedback, limb mechanics, muscular strength, fatigue, and even emotional state to produce the most efficient strategy available in the moment, automatically (Kelso, 1995; Loeb, 2021). This ability to self-organize movement is based on a larger motor control concept called Dynamic Systems Theory (Kelso, 1995).

That’s why people naturally adopt different lifting styles without instruction—their brains have already “tested” variations through experience and settled on a movement that feels safe and efficient given their current physical state (Loeb, 2021). Could we override that instinct by consciously “keeping the back straight” or “lifting with the legs”? Sure. But doing so might conflict with the body’s own adaptive strategy—especially if pain or stiffness is present (Hartvigsen et al., 2018). Sometimes, forcing a textbook posture increases strain instead of reducing it (von Arx et al., 2021).

So… Should You Lift With Your Legs?

The answer is: sometimes. If someone has pain bending forward, encouraging a squat-style lift can help (Hartvigsen et al., 2018). If flexion feels fine but extension hurts, stoop or freestyle lifting may be better (Fujii et al., 2022). And if someone naturally uses a mixed style without pain, there’s little reason to “correct” them. Ultimately as clinicians we can focus on improving strength as people with stronger hips, backs, and cores tolerate all lifting styles better (Hartvigsen et al., 2018).Perhaps more important than trying to coach an individual into always maintaining a perfect posture when lifting is focusing on load management, movement confidence, and physical conditioning. Teaching fear-free movement and gradually restoring trust in the body often makes more difference than enforcing rigid form (Hartvigsen et al., 2018).

The Take-Home Message

Many long-held beliefs about “the right way to lift” come from outdated or oversimplified ideas about spinal mechanics (Adams & Dolan, 1996; Gallagher & Marras, 2012). Human movement is adaptive, resilient, and incredibly individualized (Kelso, 1995; Loeb, 2021).

- The safest lift depends on the person, not the rulebook (Hartvigsen et al., 2018).

- Pain doesn’t always equal damage—it’s the nervous system’s protective response (Kuner & Flor, 2021; Yuan et al., 2024).

- Spines are strong, and movement variation is healthy (Adams & Dolan, 1996).

- Coaching should focus on confidence, conditioning, and context, not fear of “bad posture” (Hartvigsen et al., 2018).

So next time someone bends to pick up a box and doesn’t use the “approved” squat form, resist the urge to correct them. They may be doing exactly what their body is designed to do—move efficiently, adaptively, and safely in the way that works best for them (Kelso, 1995; Loeb, 2021).

In short:

“Lift with your legs” isn’t wrong—but it isn’t always right either. The smartest way to lift is the one that fits the person, the task, and the moment (von Arx et al., 2021).

References

Adams, M. A., & Dolan, P. (1996). Time-dependent changes in the lumbar spine’s resistance to bending. Clinical Biomechanics, 11(4), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/0268-0033(96)00002-2

Armstrong, C. M., & Herr, D. H. (2023). Neural mechanisms of nociceptor sensitization and pain modulation in human peripheral afferents. Nature Neuroscience, 26(4), 512–524. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-023-01345-7

Bae, K., Lee, S., Bak, S.-Y., Kim, H. S., Ha, Y., & You, J. H. (2024). Concurrent validity and test reliability of the deep learning markerless motion capture system during the overhead squat. Scientific Reports, 14, 29462.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79707-2

Brinjikji, W., Luetmer, P. H., Comstock, B., Bresnahan, B. W., Chen, L. E., Deyo, R. A., Halabi, S., Turner, J. A., Avins, A. L., James, K., Wald, J. T., Kallmes, D. F., & Jarvik, J. G. (2015). Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. The Spine Journal, 15(6), 1106–1117.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2015.02.001

Fujii, K., Yamada, T., & Nakamura, M. (2022). Morphologic changes and canal narrowing in lumbar spinal stenosis: A quantitative imaging study. The Spine Journal, 22(6), 881–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2022.02.015

Gallagher, S., & Marras, W. S. (2012). Tolerance of the lumbar spine to shear: A review and recommended exposure limits. Clinical Biomechanics, 27(10), 973–978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2012.08.004

Hartvigsen, J., Hancock, M. J., Kongsted, A., Louw, Q., Ferreira, M. L., Genevay, S., Hoy, D., Karppinen, J., Pransky, G., Sieper, J., Smeets, R. J., Underwood, M., & Lancet Low Back Pain Series Working Group. (2018). What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. The Lancet, 391(10137), 2356–2367. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X

Hodges, P. W., & Tucker, K. (2011). Moving differently in pain: A new theory to explain the adaptation to pain. Pain, 152(3), S90–S98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.020

Kelso, J. A. S. (1995). Dynamic patterns: The self-organization of brain and behavior. MIT Press.

Kirkaldy-Willis, W. H., & Farfan, H. F. (1982). Instability of the lumbar spine. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 165, 110–123.

Kuner, R., & Flor, H. (2021). Structural plasticity and reorganization in chronic pain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 22(2), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-020-00392-7

Lam, T., Cates, L., Wälchli, M., Metcalfe, A., van Welie, K., & Clarke, S. T. (2023). The influence of the marker set on inverse kinematics results to inform markerless motion capture annotations. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 20, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-023-01186-9

Loeb, G. E. (2021). Learning to use muscles. Journal of Human Kinetics, 76, 9–33. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2020-0084

Lopez-Gonzalez, M. J., Ortega-Serrano, J., & de la Cruz, F. (2022). Temporal summation and delayed-onset pain flares in musculoskeletal loading: Experimental observations in humans. Pain Reports, 7(1), e1012.https://doi.org/10.1097/PR9.0000000000001012

Noailly, J., Galbusera, F., & Wilke, H. J. (2023). Load transfer and facet joint mechanics in lumbar spine degeneration: A computational investigation. Journal of Biomechanics, 150, 111598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2023.111598

Park, S., Lee, J., Kim, Y., & Choi, H. (2024). Finite-element analysis of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration and its impact on adjacent segment mechanics. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 12, 1384187.https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2024.1384187

Schreiber, K. L., et al. (2025). Recognizing pain phenotypes: Biopsychosocial sources of variability in pain. (In press.)

van der Graaf, J. W., Kroeze, R. J., Buckens, C. F. M., Lessmann, N., & van Hooff, M. L. (2023). MRI image features with an evident relation to low back pain: A narrative review. European Spine Journal, 32, 1830–1841.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07602-x

von Arx, L., Liechti, M., Meier, M. L., & Schmid, S. (2021). From stoop to squat: A comprehensive analysis of lumbar loading among the main lifting styles. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 9, 622148.https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.622148

Yuan, Y., Lin, Z., & Zhang, L. (2024). Central sensitization and synaptic plasticity in chronic low back pain: Insights from neuroimaging and animal models. Brain Sciences, 14(2), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14020159