The COVID-19 vaccine is finally rolling out to the masses, and it couldn’t be more exciting. After nearly a year of reduced socialization, stringent infection control protocol, and increasingly dire news cycles, there’s a light at the end of the tunnel! Herd immunity (by way of vaccination) looks to be less than a year away, and we deserve to celebrate that win—albeit while continuing to social distance and shelter in place for now. But, we’d be doing a huge disservice to our peers, our communities, and our country not to address the healthcare inequities that this vaccine rollout has brought to the forefront.

The COVID-19 vaccine rollout has been bumpy—at best.

Now, don’t get me wrong—I recognize that devising a national vaccine rollout program from scratch (one that needs to deploy in under a year, no less) is one hell of a hoop to jump through. While I’d like to believe there was a possible future where Operation Warp Speed went off without a snag, it seems the cards were stacked against us. That’s because:

- There was no clear distribution strategy outlined by the federal government for one of the largest vaccine efforts in US history;

- Much of the work and distribution planning fell on state governments, which were underfunded and unprepared to tackle this challenge;

- The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) wrongly inflated its vaccine supply estimates, shorting some states up to 40% of the doses they expected;

- Tight vaccine administration requirements limited states’ ability to distribute the vaccines they had access to, causing some supplies to expire;

- Many hospitals are understaffed and overworked due to splitting their workforces between COVID-19 patient care and vaccine administration;

- The Biden transition team only gained access to critical vaccine distribution software in mid-January, reducing their ability to effectively create their own distribution plan.

Expansion of the vaccine rollout amplified some of these problems.

The federal government’s decision to expand the rollout effort—while a crucial move to make—has only exacerbated some of these issues. Hospitals and vaccine distribution sites that were already stretched paper-thin are being asked to complete even more vaccinations. States continue to flounder due to their lack of funds and direction. Some patients are struggling to schedule their second dose. And at this point, the federal reserve of vaccines is “effectively exhausted”—meaning states cannot assume they will receive the shipments they’ve been counting on.

You get the point.

That’s a lot of problems—and those are only the high-level problems. When you drill down into distribution statistics for specific groups of people, it’s easy to see that our current plan is not only inequitable—it’s failing the communities who need access to the vaccine most.

Minority communities face more barriers to health care—and therefore, less access to vaccines.

If you’re not already familiar with the social determinants of health, let me give you a crash course. Essentially, the idea is that people’s health (and their ability to access quality health care) is influenced by “the conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age [affecting] a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.” These social determinants of health often fall along racial lines, as much of the US never desegregated.

COVID-19 is devastating non-white communities.

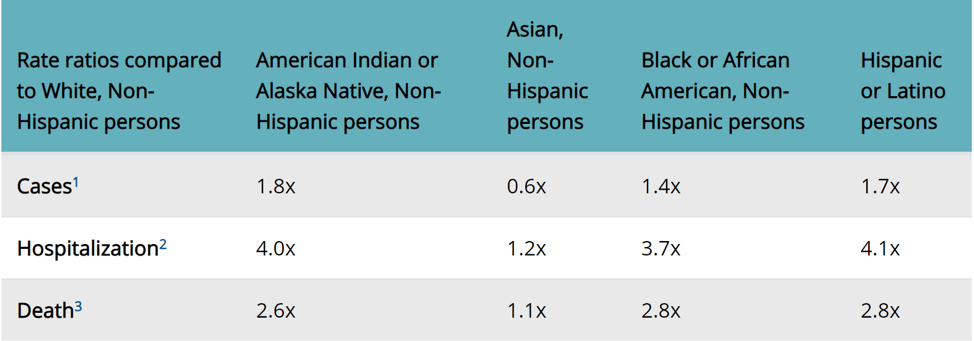

COVID-19 has hit our country hard—but it has notably hit minority communities the hardest. Just take a look at these age-adjusted case, hospitalization, and death rates provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

COVID-19 clearly poses a greater risk (sometimes up to four times) to the above-listed minorities than it does white, non-Hispanic Americans. It follows, then, that these communities should be some of the first in line to receive one of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines—but that doesn’t seem to be happening.

Yet, non-white communities are receiving disproportionately fewer vaccinations.

According to a data compilation effort by Kaiser Health News, Black Americans lag behind in vaccinations—sometimes by a shocking amount. Mississippi appears to house some of the biggest disparities: 38% of the state’s population is Black and so are 37% of its healthcare workers—and yet only 15% of administered vaccines have gone to Black Mississippians.

As COVID-19 vaccines roll out to the general public, I (and many others) hope to see those distribution gulfs diminish. However, due to historic and ongoing healthcare inequities in America, we may not see these disparities resolve themselves.

Some people are forgoing the vaccine; others simply do not have access to it.

There are many possible reasons why minority communities are not receiving vaccinations at a rate proportionate to their white counterparts—and those reasons are not necessarily rooted in the rollout plan itself. In fact, there have been many conversations about making the rollout more equitable.

However, there are two major problems that require more systemic solutions than a well-rounded vaccine distribution plan can offer:

- A number of Black and Hispanic Americans are skeptical of, and don’t immediately want, the vaccine; and

- Many marginalized communities cannot access the vaccine (or will not be able to in the future).

Distrust of the Medical Community

One reason Black and Hispanic Americans are hesitant to get vaccinated is their deep-seated (and frankly, warranted) mistrust of the healthcare system.

According to this report, only 14% of Black Americans and 34% of Hispanic Americans believe that the COVID-19 vaccine is safe. As much as I wish those fears were unfounded, they’re not. America’s healthcare system has a sordid history of mistreating minorities (just take a look at the Tuskegee experiment or our history of forced sterilizations). Beyond that, many modern healthcare workers still suffer from well-documented racial biases.

Additionally, the previously linked report found that only 28% of Black Americans and 47% of Hispanic Americans felt confident that a vaccine would be tested in their specific racial/ethnic group. Turns out, that was a perfectly legitimate concern. Both Pfizer and Moderna struggled to find Black and Latino volunteers to participate in their vaccine trials.

Vaccination Misinformation

Another reason that minorities may feel hesitant to get a vaccine? Rampant vaccination misinformation—something that has become all too common in recent years. This problem isn’t restricted to Black and Latino communities—but these untruths are no less harmful to public health. See, humans are subject to a psychological phenomenon called the illusory truth effect, in which “repeated statements receive higher truth ratings than new statements.” In other words, simply seeing anti-vax literature over and over is enough to plant a seed of doubt in someone’s mind.

Less Healthcare Access

For a variety of reasons, minorities typically have less access to health care. This may be because they’re:

- Subject to higher poverty rates,

- Less insured than their white peers, and

- More likely to live in health shortage areas.

Even pop-up COVID-19 testing sites are, in some states, disproportionately located in white zip codes. All of this is to say that our default COVID-19 response has not been universally equitable, and that could pose a real problem as the vaccine rollout continues.

The healthcare system is beholden to profitability.

Let’s shift gears from racial inequity to income and class inequality. Our medical system is, by and large, a for-profit behemoth—one that prioritizes high-quality care for those who can pay for it. This poses a unique challenge in our current situation, as the people who most need the vaccine are often the ones who can’t afford to pay a premium.

Wealthy individuals can secure vaccination priority.

Few low-income workers are able to work from home, and while many do not have the official distinction of “essential worker,” they’re still on the front lines and thus, at a higher risk of contracting the novel coronavirus. And yet, they could lose vaccination priority to wealthier Americans.

Already, doctors have begun reporting that the rich are attempting to use their wealth and influence to jump the line. And while they’ve been largely unsuccessful thus far, that will not hold true once vaccinations open to the general public. Boutique practices that serve the ultra-rich are “snapping up expensive, ultra-low temperature freezers, which are in short supply, to store the Pfizer and BioNTech vaccine…Doctors in boutique practices say they’ll adhere to public health guidelines in determining who gets priority. But being on a waiting list at a practice that has special freezers and other high-quality resources means you’re already near the front of the line once the supply opens up.”

Global Scale

We’ve already begun to see macro versions of this scenario play out on a global scale. Profit-hungry pharmaceutical companies are distributing the vaccine based on revenue potential, which means that those who live in poorer, less developed countries are being hung out to dry: “Wealthy countries representing just 14 percent of the world’s population have used their resources and influence to capture 96 percent of Pfizer’s vaccine and 100 percent of Moderna’s, according to a report by Oxfam and other human rights organizations. These nations are even planning on stockpiling extra, just in case. And because of this, it’s estimated that billions of poorer people in less-advantaged nations will not receive the vaccine for years.”

The COVID-19 vaccine is not open source (i.e., it’s patented).

Part of what drove Pfizer and Moderna to develop their vaccines at such a rapid speed was the immense market opportunity. In other words, they knew they could make money—and lots of it. Both companies have since secured patents for their vaccines, which means production and distribution are limited by what each company can manufacture on its own. It also means that they’re more likely to prioritize distributing their inventory to wealthier countries that can pay more. Already, we’ve seen wealthier countries like the US, Britain, and Switzerland team up with Pfizer and Moderna to block a World Trade Organization initiative that would allow “generic or other manufactures to make the new products.”

Moves like this stand to slow distribution and create shortages—both of which exacerbate the “highest bidder” problem. Everyone should have equal access to this vaccine (at their specific priority level), just like everyone should have equal access to baseline health care. This is potentially a matter of life or death—and it’s still being mismanaged and commoditized, further underscoring that there is something gravely wrong with our system.

Waived Patents

This is not likely to change any time soon, either. Pfizer has made clear that it doesn’t intend to release its intellectual property (IP) for the greater good. In fact, Albert Bourla, Pfizer’s chief executive, said, “The (intellectual property), which is the blood of the private sector, is what brought a solution to this pandemic and it is not a barrier right now.” And while Moderna has committed to not enforcing its patent during the pandemic, that’s a far cry from intentionally sharing IP and working with other manufacturers to rapidly distribute these vaccines as far and wide as possible.

Healthcare providers are shirking the call to protect their patients.

I’d like to make one final callout on the topic of vaccine misinformation. Many healthcare providers who have immediate access to the vaccine are choosing not to get it. This is a head-scratcher—and I would like to make it known that outside of truly exceptional circumstances, this should not be happening in PT. As physical therapists, we need to be able to have physical contact with our patients to provide our full value—and when unvaccinated, any contact we do have with patients puts them at risk. I believe it is irresponsible not to get vaccinated when you have the opportunity to do so. You’re also a doctoring, evidence-based practitioner, and this is science. Respect it. Set an example for your patients—and fulfill your oath to do no harm.

If you truly cannot receive the vaccine, mask up.

Now, I recognize that some people cannot receive the vaccine because of legitimate health concerns (e.g., immunodeficiency). If you are one of them, I empathize with you, as your risk of exposure rests in the hands of your peers. But, you can still act to protect yourself and your patients by masking up.

Honestly, this shouldn’t even be a debate anymore. We know that masks work; we know that they have few (if any) detriments; and frankly, we have way bigger fish to fry.

The vaccine rollout has cast a sobering spotlight on the inequities plaguing the American healthcare system. We have a long road ahead on our journey to address—and ultimately eliminate—healthcare inequity. Still, I think we have an opportunity to turn this situation into a massive pivot point. We have a clear picture of the inequities that ail us—and it’s time to address them. Are you in?